Over the summer, I turned twenty-seven.

Birthdays and celebrations have always thrilled me, but as I near thirty, they feel more serious than ever. I observe my friends—some getting married, others divorcing; some building businesses while others chase daydreams.

As the years pass, birthdays slowly become less about celebration and more about taking inventory of how far ahead you are in life. Of course, this would make more sense if there were an official finish line, a point where you know you’ve “made it.” Yet, there’s only one definite destination in life: death. Funny enough, death has nothing to do with self-actualization, nor does it care about it. Whether you’re done with your checklist or not, you will die.

For those who know me, that intro won’t seem strange. Rest assured, I’m not being nocturnal. There’s hope in all this—just bear with me.

In the last couple of years, we’ve been hearing the term “delayed adulthood” more frequently. It basically means that the transition from our teenage years to adulthood has been prolonged. Adulthood typically signifies agency: taking more responsibility and, as a result, having more freedom. These responsibilities include acquiring your own living space, sustaining yourself financially, deciding on the path you want to take in life, and meaningfully showing up for the people around you. But the bitter truth is that life never waits. A dying loved one or a friend in need cannot be delayed until we finish our degree or shiny new project. Meaningful moments slip by in a heartbeat.

At first, I tended to believe that everyone arrives at adulthood in their own time. In many ways, this delayed adulthood discourse didn’t make full sense to me. After all, our lifespans are longer, our quality of life is improving, and we can work and enjoy life well into old age. Having kids later in life seems like a good trade-off, so what’s the fuss? But then, it hit me. This wasn’t just about getting your master’s in your 30s or having kids in your 40s. It was about losing sociopolitical agency. This isn’t just delayed adulthood; it’s non-emergent adulthood—adulthood that never fully comes to be.

While more comfort may sound appealing on paper, it often comes at the cost of liberty. The more we trade freedom for comfort, the more we regress. And like life, regression also has one ultimate destination: childhood. As wary as we are of authoritarian leaders, we should be just as wary of the nanny state. As James Madison once said, political power is of encroaching nature. So, even if it comes in the shape of subsidies and opportunities, we must be skeptical.

Individual regression is destructive enough, but when it becomes a societal trend, it leads to decadence.

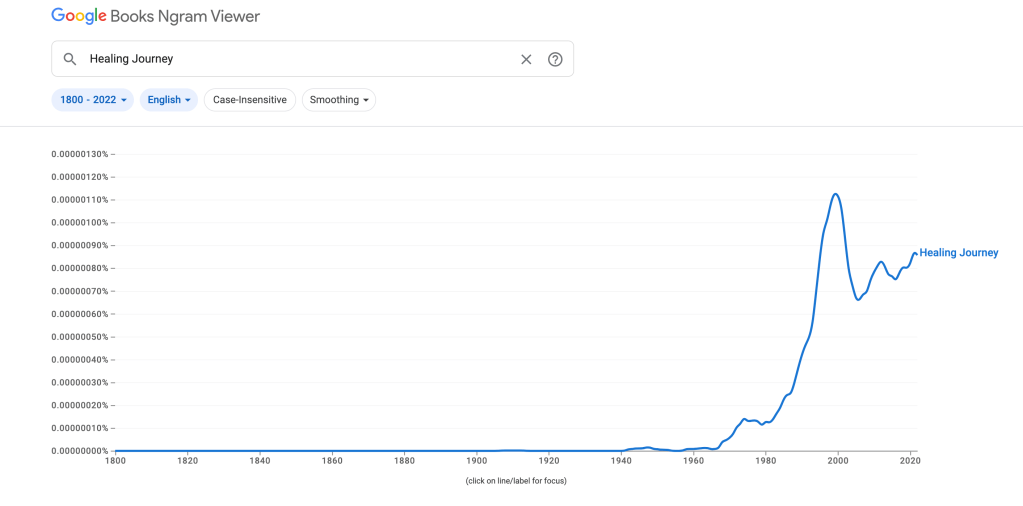

The Healing Journey

In her latest book Bad Therapy, Abigail Shrier blames this trend on the psychomedical industry. While I find her language loaded, her arguments aren’t far-fetched. My inclination, however, is to see it as more cultural.

The early 2000s were the precursor to today’s society, a time when self-help, coffee-table psychology, and similar hobbies gained traction. As we shifted from a collectivist society to a more radically individualistic one, the dizziness of freedom hit some of us hard. (I’ve always seen the law of attraction and similar concepts as more of a guiding principle than a way to fulfill desires, but that’s just a side theory.)

The world became so big and unpredictable, especially with the undoing of social norms. In response, we needed to find something stable, something solid. We became full of ourselves. I think this explains the whole “healing journey” better than the idea that almost everyone has childhood traumas so deep that all meaning in life becomes redundant.

I completely acknowledge that our younger years leave a mark on us. But I think we’ve reached a point where we blow things out of proportion to the degree that we disregard the choices we make. It seems slightly absurd to claim that a generation of people who didn’t experience forced immigration, famine, or a full-blown war is more traumatized than those who did. If previous generations were able to adapt and function at a high level, perhaps it’s not past hurt that’s causing our real problems. While I fully endorse getting psychological counseling if needed, I don’t believe therapy holds the power to cure the human condition.

The approach of seeking an expert in every aspect of life is, in my view, a rejection of agency and a decision to self-infantilize. From a liberal standpoint, I understand the importance of strong institutions, but I’m not happy with what this trend is doing to individuals.

Relationships

Following from the previous section, while I don’t think our developmental period completely shapes us, it does shape how we relate to things—people, concepts, and objects alike.

Our parents aren’t just our creators; they are the gatekeepers of life itself. Our initial life experiences happen through them, vicariously. As we get older and build autonomy, we begin experiencing life on our own. This launches the pathway to adulthood. Once our internal image of our parents is crystallized, their transformations matter less. The internal image becomes fed by universal concepts about life and death, mom and dad.

Being exposed to our parents too much or too little has a stunning effect. Either we become too preoccupied with the anxiety of losing them, missing out on life, or we remain under their shadow, never having the opportunity to come into our own.

One of my favorite verses says, “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” Preventing our kids from coming into their own is crippling, unjust, and cruel.

This type of relationship dynamic is, unfortunately, something I see often. I hate to admit it, but I’ve spent time in the manosphere, and in terms of needs, if Maslow had a secret basement on his pyramid, that’s where these people would be. I generally have a soft heart and understand where they’re coming from, but that doesn’t mean I condone their ways. They do, however, make for a great case study of individuals whose primary needs were never met.

I see relationships, especially romantic ones, as the best way to self-actualize. Our biggest source of meaning comes from our people—our person.

But when we fail to carry our weight in relationships, the other person becomes an object rather than an individual. When we’re starving, everything looks like food. Lacking agency as an adult leads to extremes: either childish entitlement or hyper-independence. Neither extreme leads to quality relationships, and without quality relationships, growth stagnates, and we end up running in circles.

I hate to speak in ideals, but a good relationship stands on three pillars: practical, social, and mystical. We usually get stuck on one or the other.

Nowadays, socialisation has less to do with survival and more to do with thriving. Naturally, when people lack community or avoid socialisation due to voluntary or involuntary reasons we skip a beat in having meaningful growth. Which results in another path to adulthood being blocked.

Rituals

Returning to where we began: birthdays. Birthdays, christenings, funerals, and weddings. We need them all.

As a kid, I hated weddings—especially the big ones. But as an adult, I now see the practicality and importance of rites and rituals.

Rituals help us mark clear distinctions between the past and the future, ensuring smooth transitions between roles. They resolve ambiguity and make a public declaration to society about the new role you’re stepping into. While grieving a loved one I learned about death doula’s which shifted my perspective on our last farewell. They also help our pain be seen, acknowledged, and processed, allowing us to grow beyond it. In this sense, I find rituals and community to be more important than therapy ever could be.

It seems to me that the lack of rituals is why people categorize themselves to the moon based on aesthetics or singular personality traits, doubling down on them. Rituals allow us to be fully human, individualises us rather than reducing us to one-dimensional beings with syndromes or labels.

Perhaps we should embrace those big, exhausting weddings.

To Conclude

Taking inventory of your life is all well and good—helpful, even, as long as it doesn’t lead to rumination. But adulthood and agency don’t lie in goalposts and metrics. They lie in the questions we regularly avoid. No one can die our death for us and no one can answer our big questions in our name.

Look into your own abyss, and then come back to me.

References

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2009). The emergence of adulthood: A global perspective. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2714655/

- Douthat, R. The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success.

- Arslan, H. (2022). Delayed Adulthood in Sociocultural Context: A Comparative Analysis. Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/3682054

- Warzel, C. (2024, September 15). Helicopter parenting or ignoring? An Opinion Piece on Modern Parenting. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/15/opinion/parenting-helicopter-ignoring.html

- Gioia, T. (2024). 13 Observations on Ritual. The Honest Broker. Retrieved from https://www.honest-broker.com/p/13-observations-on-ritual

- Ozgur, S. (2024, March 26). Big Things Are Over. Retrieved from https://salpiozgur.com/2024/03/26/big-things-are-over/

Leave a comment